Preface: This article

is written solely for the purposes of education and cultural interest. I do not

necessarily condone nor encourage anyone to partake in these kinds of rituals.

|

Cartoon depiction of

a Beating Petty Persons Ritual

(Image: Apple Daily 蘋果日報) |

Beating Petty Persons

(打小人

Mandarin: Da Xiaoren; Cantonese: Da Siu Yun) is a form of southern

Chinese folk sorcery that is popular in Guangdong

province and Hong Kong. Da (打)

means to beat or to hit, and a xiaoren (小人) literally

means a small or petty person which refers to someone who causes grief, trouble, or anger

to others. It is also sometimes translated as vile person or villian. A

xiaoren could be an ordinary person like a personal rival, a problematic

neighbor, a nasty boss, a backstabbing coworker, or an irritating customer. Or it

could be somebody famous like an unpopular politician or a Public Enemy Number One.

The basic idea of the ritual is to use a shoe or other

implement to beat a paper effigy representing a targeted person (the “petty

person”) to bring him or her harm, so that the petty person no longer brings

trouble to the one who requests the ritual. To put it another way, it is a form

of Asian voodoo magic.

People who perform this folk ritual as a professional career

are traditionally elderly women, although in recent times, a small number of younger

women have also taken up this profession.

To perform the ritual, the professional petty person beater goes through the following general steps (with

some variations depending on the individual practitioner):

1. Make Offerings to the Deity (奉神 feng shen)

Incense and candles are first offered to the deity installed

in the practitioner’s shrine. This introductory act is to request and enlist

the deity’s help in order to make the ritual successful.

In the case of streetside practitioners who offer their

services at a public area out-of-doors, the shrine is usually a make-shift

shrine consisting of a cardboard box containing a porcelain statue of any

popular deity from Chinese folk religion.

|

Makeshift shrines

for the Beating Petty Persons Ritual

(Image: Original

source unknown)

|

2. Make a Report/Petition to the Deity (稟告神明 binggao shenming)

The petty person beater gets the name and birth information

of the client and writes it on a ritual paper.

She then asks the client to identify the targeted person

(petty person). If the client has a particular person in mind, then that petty person’s

identity is noted on a paper effigy, along with some or all of the following –

name, gender, address, birth information, photo, and a piece of the person’s

clothing.

If the client does not have anyone specifically in mind, then

he or she is only seeking the ritual as a general blessing to keep away potential

petty persons.

The petition is then presented to the deity in the petty

person beater’s shrine.

|

A professional beater’s religious shrine

(Image:

Ta Kung Pao News 大公报) |

Important Sidenote:

At this point, I feel that it is important to include a personal comment here.

It is common to see an image of Bodhisattva Guanyin (觀音菩薩 Guanyin Pusa; Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara) in the shrines used by

petty person beaters. Bodhisattva Guanyin is a much beloved religious figure in

Chinese religion. She is equally venerated by Buddhists, Taoists, and followers

of popular folk religion as well. But her origin is from Mahayana Buddhism

where she is regarded as a fully enlightened buddha. The compassion and wisdom

of Guanyin is all-encompassing, so according to an orthodox Buddhist

perspective, the inclusion of a Guanyin image (or any other Buddhist figure for

that matter) in a ritual for bringing harm to others is definitely inappropriate

and a badly-conceived concept. I believe it’s also safe to say the same thing

for any other orthodox Taoist deity that might also be used. But I digress…

3. Beat the Petty Person (打小人 da xiaoren)

A set of petty person

ritual papers (小人紙 xiaoren zhi) is prepared which

will serve as an effigy for the targeted person (or the general idea of a petty

person if there is no particular person specified).

The common set of effigy papers generally consists of a male petty person ritual paper (男小人紙 nan xiaoren zhi) and/or a female petty person ritual paper (女小人紙 nu xiaoren zhi) wrapped in a five ghosts ritual paper (五鬼紙 wugui zhi).

|

A woman shows a set of petty person ritual papers

(Image:

Apple Daily 蘋果日報) |

The petty person beater places the paper effigy on a brick,

and then uses a shoe, slipper, or some other form of symbolic weapon to repeatedly

strike the paper effigy while reciting Cantonese rhyming verses that are vile

and intended to send harm to the petty person. The brick is a very hard object,

so by association, it brings more pain to the petty person. It is also said

that a shoe or slipper that has been previously worn brings more power to the

ritual.

|

A woman beating a petty person effigy with a slipper

(Image:

Guangzhou Daily

廣州日報) |

|

A professional petty person beater

(Image:

Apple Daily 蘋果日報) |

4. Offer Sacrifice to the White Tiger (祭白虎 ji baihu)

Raw fatty pork, sometimes dipped in pig’s blood, is offered

to a paper effigy representing the malevolent White Tiger. Sometimes, grease

from the fatty pork is also smeared on the paper tiger’s mouth.

|

In the foreground, representations of the White Tiger

are offered raw fatty pork

(Image:

Apple Daily 蘋果日報) |

|

A paper effigy of the White Tiger is offered raw fatty

pork

(Image:

Oriental Daily News 東方日報) |

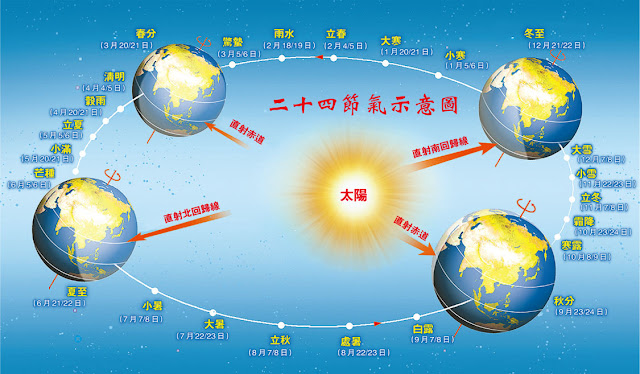

This step is sometimes omitted, but it is especially

important if the day happens to be Jingzhe

(驚蟄),

the third term of the Twenty-four Solar Terms

(二十四節氣

Ershisi Jieqi) in the Chinese lunisolar

calendar.

|

Jingzhe−Insects awaken, the third of the Twenty-four Solar Terms

(Image: Original source unknown, edited by Harry

Leong)

|

Jingzhe means Awakening of Hibernating Insects, and indicates

when the spring weather is warming up. This day is when the sun reaches a

celestial longitude of 345°. It falls on March 5th or 6th

of the Western Gregorian calendar. According to legend, the first thunderstorm

of the year will awaken hibernating insects on this day, as well as stirring up

certain negative forces that are represented by the White Tiger. In ancient

times, it was customary for people to offer religious sacrifice to the White

Tiger spirit on this day to keep its forces at bay. The custom of offering sacrifice to the White Tiger and the

practice of Beating Petty Persons were somehow gradually merged, and thus,

Jingzhe also became the most popular day for people to request the Beating

Petty Persons ritual. It is also believed that the ritual is most effective on

this particular day.

5. Dispel Negativities (化解 huajie)

The petty

person beater may scatter

rice, beans, sesame seeds, or a combination of these, to get rid of

negativities. She may also use a Talisman

for dispelling a hundred obstacles (白解符 baijie fu) and wave it over the client’s body and burn it for

removing obstructions.

|

A woman scatters sesame seeds and beans to get rid of

negativities

(Image:

Hong Kong Memory 香港記憶 hkmemory.org) |

|

An example of a Talisman

for dispelling a hundred obstacles

(Image:

Travel18.net)

|

6. Pray for Blessings (祈福 qifu)

A red Talisman of noble persons (貴人符 guiren fu) is placed into the hands of the client and then it is burned

to attract helpful people.

|

An example of a Talisman

of noble persons

(Image:

Collection of Harry Leong) |

7. Offer Treasures to the Deity (進寶 jinbao)

Joss paper

representing gold and silver (金銀衣紙 jinyin yizhi) are burned as gifts of appreciation for the

deity’s help.

8. Consult the Crescent Moon Divination Blocks (擲筊 zhi

jiao / 打杯 da

bei)

The petty person beater then uses the crescent moon

divination blocks (筊杯 jiaobei) to ascertain if the ritual was successful or not.

The crescent moon blocks are held and then dropped to the ground in front of

the deity shrine. If the blocks land with one facing up and one facing down,

then it is accepted as a positive response and the ritual is considered

complete. But if the blocks land both facing up or both facing down, then it is

a negative answer and the ritual procedure must be repeated again.

A set of crescent moon divination blocks

(Image: Original source unknown)

In Hong Kong, a

well known hotspot where professional petty person beaters congregate and offer

their services is underneath the Canal Road Flyover (堅拿道天橋 Mandarin: Jianna Dao Tianqiao;

Cantonese: Gin Na Dou Tin Kiu) in Wanchai district. Locals call the flyover Goose Neck

Bridge (鵝頸橋 Mandarin: E’jing Qiao;

Cantonese: Ngor

Geng Kiu). The area underneath the flyover is at the

intersection of several roads, which feng shui deems the ideal place for

dispersing negative energies.

|

Underneath the Goose Neck

Bridge (Canal Road Flyover)

in Wanchai, Hong Kong

(Image:

Original source unknown) |

|

A professional petty person beater underneath the Goose Neck

Bridge

(Image:

Oriental Daily News 東方日報) |

There are two main views concerning the nature and efficacy

of the ritual that are shared even by the professional beaters themselves. One view

is that the ritual merely serves as a psychological outlet for people who feel

anger towards their enemies. The performance of the beating ritual helps them

release this anger and provides them with a renewed sense of confidence for

dealing with difficult people. The other view, held by those that take the

ritual seriously, is that it really does have the power to inflict harm and

stop troublesome people in their tracks.

|

A client watches on as a professional beater performs

the ritual

(Image: Apple Daily 蘋果日報)

|

The Ritual of Beating Petty Persons has become so famous

that according to Time magazine’s The Best

of Asia 2009, the ritual was described as the “best way to get it off your chest.”

In 2014, the Hong Kong Home Affairs Bureau officially

released its list of Intangible Cultural

Heritage of Hong Kong (香港非物質文化遺產 Xianggang Feiwuzhi Wenhua Yichan) which included

the Beating Petty Persons Ritual because it is considered to be a part of Hong Kong’s ancient traditions and living culture.

Text © 2016 Harry Leong